If you’ve read Summer Sorcery, you’ll know that I’m a little in awe of the humble Brownie. If you haven’t yet read it, well…

For those not in the know, I’m not referring to the small square cakes of chocolatey goodness. The other kind of brownie is a being from Scottish mythology. They’re household spirits that delight in maintaining order and tidiness within a home. Traditionally, they live in hearths and other warm nooks. So the stories would have it, brownies accept offerings of food as payment, but are highly offended by other gifts or attempts at payment. Sound familiar?

Brownies in modern fiction

I’ve read in enough places to simply accept as fact that brownies are the inspiration for house-elves from that other series of books about a wizard. You know the one. That said, brownies are most certainly not house-elves. Brownies of traditional Scottish mythology are the proud custodians of a homestead. Magical caretakers, not servants. They may be small, but they are not infants in either behaviour or speech. Brownies are smart and resourceful. Though limited by their size and talents, they are distinctly a force to be reckoned with.

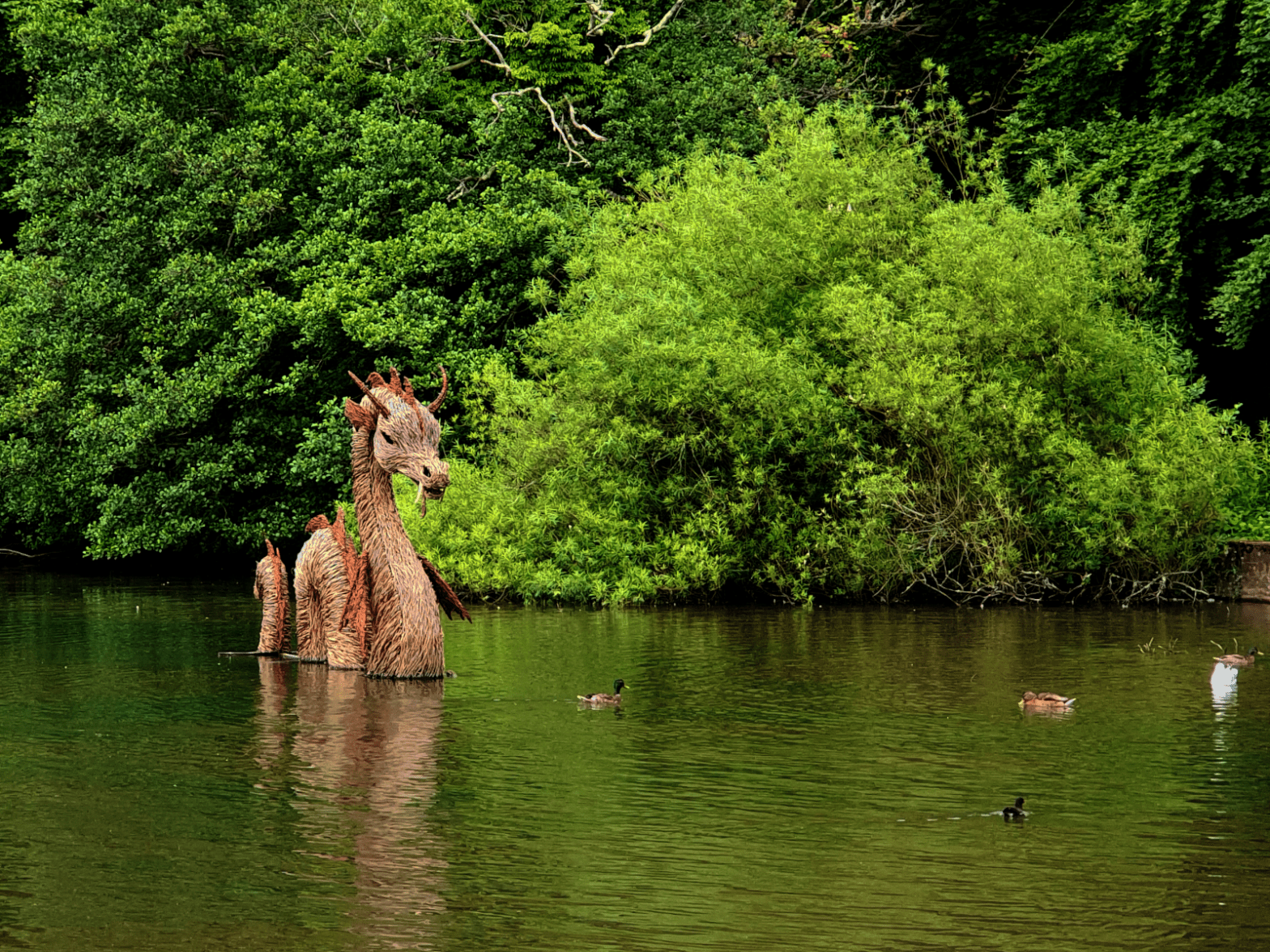

Significantly closer to traditional brownies is their presentation in Wolf Notes, by Lari Don (Book 2 in her ‘First Aid’ for Fairies series). Here they appear as janitor custodians that defend Dunvegan Castle from interlopers, despite the intruders including a dragon and a centaur.

Domovoi

The Domovoi

Where things got interesting for me was the striking parallels that are completely disconnected from Scottish folklore. The first one I stumbled upon was the domovoi in The Bear and The Nightingale by Katherine Arden. (Health warning: not a children’s book. Brilliant, though.) Domovoi are house-spirits from Russian folklore. According to legend they live in the embers of the oven, and come out at night to tend to the home, repairing broken things and tidying away clutter. Incidentally, traditional Russian ovens are enormous affairs which are large enough for the family to sleep on in the winter,

This parallels quite nicely to the brownie’s traditional abode of hearths and inglenooks, cosy sitting areas within a large fireplace. In Scotland’s Western Isles, it was customary to bank the fire at night but leave some embers burning to keep the brownies warm. The Roman Di Penates were similarly connected to fireplaces. Offerings of food would be thrown into the hearth by the family to keep their household gods happy. A little more on these guys later.

Fireplaces

Which brings us to what is probably my favourite part. An old British tradition (when domestic fires were still the normal mode of heating) was that when members of a household would move out, embers from the fireplace would be carefully taken and brought to the new home, where they would be installed to heat the new house. This was thought to keep the family ties unbroken. This tradition is what gives us ‘housewarming’ gifts, a tradition that is still very much alive and well.

Given that brownies reside in exactly those embers, I can’t help but wonder if some of the brownies might opt to be transferred with them, maintaining the more mystical family ties as well.

Magical Protectors

Brownies and their international kin aren’t always just custodians in a janitorial sense. When the situation demands they will defend their homestead. In the case of Domovoi and brownies themselves this would usually be by covert means, scaring away intruders by startling their horses, or generally being creepy at the intruders themselves. However, some domestic sprits can be much more proactive.

The Romans’ notion of domestic spirits Di Penates were considered as household-gods and would be frequently called upon in various domestic rituals. Shrines would be built to them in the innermost part of the house, where they would guard the family’s food, drink and other supplies. They are sometimes referred to as tutelary deities, that is protector-gods. Certainly a more ferocious role than that of the brownie, but perhaps the ancient roman empire was a more hazardous place to live than ancient Scotland.

In a similar vein, Chinese tradition has the mên shên, the door-gods. An old legend relates that within the branches of an enormous peach tree, growing on the slopes of Mount Tu Shuo, was the Door of the Devils, through which malicious spirits would cross into our world. Eventually, the Door was guarded by two spirits. The good kind, presumably, though they may have just been looking for a fight. Their duty was to capture those spirits who had harmed humans. The evil spirits would then be bound and fed to tigers.

All this led to the legendary Yellow Emperor, Huang-Ti, to have portraits of the two spirits painted onto peach-wood panels. These were to be hung above the palace doors to ward off evil spirits. I don’t know if legend tells whether or not the paintings work as wards, but mên shên are apparently still hung on doors throughout China. Make of that what you will.

Might or wit?

Straying back to Scotland, our very own brownies may seem tame compared to the might of their foreign counterparts. But perhaps what they lack in strength they make up for with cleverness, defending their home in the manner of Kevin from the Home Alone movies. In Summer Sorcery I had fun taking this notion to its logical (or not) extremes, allowing brownies some magical tidying capabilities, inducing objects to pack themselves away neatly. It would not be too hard to imaging a burglary being hampered by a well placed paddling-pool which, on being accidentally stepped in, might fold itself up around the unsuspecting intruder. I expect they would have many more such tricks.

Legends tell of a last resort that brownies may call on. In a few tales, if offended or threatened sufficiently, brownies have been known to turn into a boggart — an entirely less friendly being. According to folklorist Katharine Briggs in her Dictionary of Fairies, a boggart is ‘almost exactly like a poltergeist in his habits.’ That magic word ‘almost’ gives us a little wriggle room, and she doesn’t clarify exactly how a boggart is unlike its Germanic counterpart. I’m not sure finding out would be worth the risk, though. It’s far easier to just be polite and keep our brownies happy.

This is far from an exhaustive look at brownies, let alone their varied kinfolk from abroad. If there’s anything I’ve missed, I’d love to read about it in the comments.