I’ll admit to these magnificent sea-dwellers being something of a blind spot for me. While I grew up with tales like ‘The Kingdom of the Seals’ (from the worn out tape of my much loved issue 24 of Storyteller magazine), my interest in selkies didn’t properly take root until a few years ago. My children are voracious consumers of stories and it has always been my pleasure to read to them. (I suspect I’ll have to stop one day, but I try not to think about it.) A while back, my daughter and I shared the Magnus Finn adventures, A trio of exciting (and a bit scary) adventures about a half-selkie boy. Well worth a read, but not for the faint-hearted.

Since then I’ve been on the lookout for stories about those most Scottish of mythological beings, and I haven’t been let down. Tales abound, riffing on a few central themes, but creating a vibrant mythology about the Seal Folk.

So what is a selkie?

Well, first of all, a selkie is not a mermaid. We have those too. Indeed, there are tales of cooperation between the two. We’ll get to that in a bit.

Simply put, a selkie is a seal that can cast off their skin to take on a human form. So a shape-shifter of sorts, but in a specifically limited way. The important detail is that the seal-skin is the key to this transformation. Without it, the human-shaped selkie is unable to return to the sea.

Naturally, it is this that creates the central conflict in many of the stories. And it’s here that folktales again shine their light on the darker side of humanity. Perhaps the main theme in selkie tales is that of the Seal Maidens — beautiful young women discovered, dancing on a beach by night or some such, a young man steals a seal-skin and claims the owner as his wife. Without it the poor selkie lass is unable to return to her beloved sea. Eventually, she recovers her skin and makes her escape, usually not before having many children with her captors. Frequently it is those children who, unwittingly, find the seal-skin for their mother.

Yup. Another tale of men subjugating women and calling it love. In fairness, the stories usually don’t end happily for the men. However, in my view, they get off far too lightly. Still, the take-home message is solidly ‘don’t be that guy.’ I suppose we have to start somewhere.

Selkie-men have a slightly different place in the lore. They too have relationships with humans, albeit more willingly. In ‘The Great Selkie of Sule Skerry’, a man has a baby with a young woman. The useless cad scarpers, leaving her with no husband and a son with webbed hands and feet. Move on a few years and selkie-git pitches up at the beach in his seal form. He shows the boy how to transform into a seal, gives him a gold chain so his mum can recognise her son, and takes the lad out to sea leaving the poor woman understandably bereft. Eventually, she finds a husband. An altogether more decent chap. They have a good life for a while, until one day he comes home with the strangest tale… He was out hunting and saw a pair of seals a large male and his pup. The pup was wearing a gold chain. Being the mighty manly chap that he was, he promptly shot them. Sometimes I’m a bit ashamed to be a man.

Selkies and mermaids

On that joyful note, let’s take a look at selkie dealings with their (more widespread) sea-friends the mermaids.

One day a Shetland fisherman caught and skinned a seal who turned out to be a selkie (seriously guys, lets to better!) Ashamed by his actions he threw the body back into the sea. Cold and broken the selkie made his way to a nearby mermaid’s cave. She knew the only cure was to get his skin back so the mermaid raced to the fishing boat and grabbed the nets. When the fisherman drew her in he was horrified that he’d caught a mermaid. He wanted to release her with the skin, but his mates insisted taking her to shore and selling her. (Seriously? Guys, come on.) The mermaid, who can’t stand living in air for long, dies as she knew she would. In Orkney and Shetland tradition, the death of a mermaid summons a huge storm. The fishing boat sank with all hands and as the mermaid hoped, the selkie-skin drifted down to her cave where her friend regained it and was healed.

Apparently, it is also a traditional belief that a selkie’s blood, if shed in the sea, will summon a great storm. Presumably the fisherman did a very clean job of skinning the seal.

Softer Traditions

Just to complicate things, we have slightly different traditions on the mainland. Here the Seal Folk are also called the Roane. Whereas the Selkies wreak revenge on seal-catchers with wild storms to sink ships, the Roane take a softer approach as characterised in the Kingdom of the Seals.

A hunter from John O’Groats came upon a large seal. He crept up, drew his knife and stabbed the creature in its neck. His strike was not good and the seal twisted into the water, wrenching the knife from the hunter’s hand.

That night, a stranger came to the hunter’s cottage conveying a large order for seal skins. The hunter was to go with the messenger to his master to finalise the deal which was for a great deal of money, so the hunter followed the stranger out into the night.

Before long they reached an abandoned cliff over the sea and the hunter, not being the sharpest knife in the drawer, began to get suspicious.

“Where is your master?” he asked.

“Down here,” said the stranger. He grabbed the hunter and leaped from the cliff.

As the cold water rose around them, the stranger’s body turned into a seal. The hunter was shocked to see that he too had transformed. The stranger led him down into the depths where they came upon a city of Seal Folk. The stranger led the hunter to a dwelling which contained the seal, injured by the hunter.

The stranger raised an object, the hunter’s lost knife, and said, “do you recognise this?”

The hunter was struck dumb by fear and remorse and merely nodded.

“That is good,” said the stranger, “for now you can undo the ill you have done. Place your hands on the wound.”

The hunter did as he was told and to his amazement the wound was healed.

“I will return you to your family,” said the stranger, “but only if you promise to never again harm a seal.”

The hunter of course promised and was led first to the cliff, then back to his house. The stranger gave him a large sack of money — more than the hunter would earn in a year of killing seals.

For his part, the hunter was as good as his word and better. Not only did he never again hunt seals, but instead did all he could to protect them.

An Ongoing Tradition

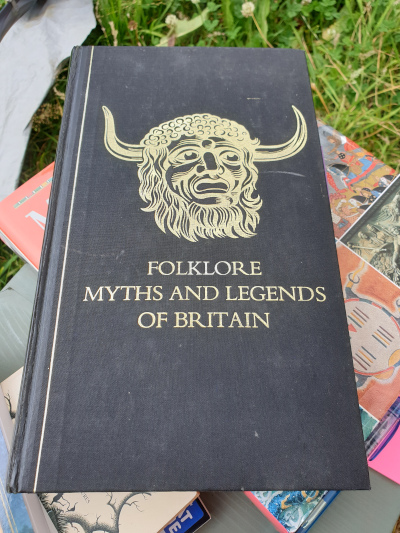

While researching this article I came across a couple of snippets about selkie belief leaking out into the (almost) modern world from the wonderful Folklore, Myths and Legends of Britain, published in 1973 by Reader’s Digest. It is a fabulously readable exploration of our traditions and tales and well worth it if you can get hold of a copy.

One item that caught my eye: a wee side-note that Clan MacCodum of North Uist are known as ‘Sliochd nan Ron’ — the Offspring of Seals. It is claimed that a distant ancestor married a seal-maiden in the usual manner, and their children gave rise to the clan as it now is. The title is delightfully taken up in the Magnus Finn stories, which is always something I love to discover in modern books.

A related but more specific account is of a woman from 1895 named Baubi Urquhart. She claimed, apparently in all seriousness, that her great-great-grandfather married a seal, and that she was a direct descendant of that union.

Traditions from elsewhere

Annoyingly, this is where my research skills ran out. Unlike the brownies, who seem to have cousins all around the world, I haven’t found much more of a family tree for our dear Seal Folk. I suppose I shouldn’t be surprised. After all, households are more widespread than seals. That said, I’m sure I’ve missed plenty. Let me know in the comments if you come across anything, please.